Over the years, I’ve had countless conversations where people ask whether prosciutto or other cured meats are considered “processed.” After making and tasting prosciutto in Italy, and curing my own versions at home, I realized how much confusion there is around this simple question.

Prosciutto looks delicate and refined, but it’s also one of the oldest preservation methods in the world. When you understand how it’s made—just pork, salt, air, and time—it doesn’t fit neatly into the same box as the industrial products most people think of when they hear the term “processed meat.”

Charcuterie, as a craft, is about transforming meat using salt, spices, and controlled drying or cooking. I’ve always seen it as an art form that connects flavor, preservation, and patience. Still, the word “processed” is used by different organizations, each with its own interpretation. That’s where most of the confusion begins.

Defining Charcuterie and Processed Meat

Charcuterie covers a wide range of meats, from the dry-cured salamis hanging in Italian cellars to the smooth pates and rillettes found in traditional French butcheries. Each one involves a process, but not all of them fall under what the health authorities call “processed.”

Charcuterie can be dry-cured meats such as salami, prosciutto, and pancetta. These are typically made by hand, with minimal ingredients, and preserved slowly over time.

In the traditional French sense, charcuterie also includes cooked preparations like ham, terrines, or offal-based dishes such as pâté and rillettes. These are crafted for flavor and texture as much as preservation.

From an Italian perspective, the term salumi overlaps with charcuterie and includes both whole-muscle cures and salamis. Salumi traditions focus on simplicity—salt, pork, and the right environment.

How Processed Meat Is Commonly Defined

Depending on who you ask, “processed meat” can mean very different things. That’s one reason the debate never ends. Some organizations define it based on preservation method, while others focus on additives or chemical treatments.

The American Institute for Cancer Research describes processed meat as “meat preserved by smoking, curing, or salting, or by adding chemical preservatives.”

The World Health Organization’s broader definition includes meat that has been “transformed through salting, curing, fermentation, smoking, or other processes to enhance flavor or improve preservation.”

It’s easy to see how these broad terms create confusion. By those definitions, nearly every cured or smoked meat—from salami to traditional bacon—could be labeled “processed.” Yet, in practice, there’s a vast difference between a handcrafted Parma ham and a mass-produced hot dog.

After studying cured meat production across Europe, I’ve learned that “processing” in the artisanal sense is about care, not shortcuts. It’s not about stabilizers or color enhancers—it’s about time, airflow, and a respect for the ingredients.

Charcuterie vs Processed Meat — Key Differences

After spending decades making charcuterie and studying different curing traditions, I’ve come to see a major gap between how authorities define “processed meat” and how artisans like myself actually use that term. In the food industry, it’s often used as a broad category that lumps together everything from Parma ham to hot dogs. But those two couldn’t be more different.

Processed meats, in the commercial sense, are usually made in large factories with stabilizers, binders, and additives. Charcuterie, on the other hand, focuses on the minimal use of ingredients and relies on salt, natural drying, and time to create something that’s both safe and deeply flavorful.

This difference isn’t just about taste—it’s about philosophy. One is about speed and preservation at scale, while the other is about patience and craftsmanship. When you make charcuterie, you’re not adding ingredients to extend shelf life; you’re creating conditions that allow nature to preserve the meat safely over time.

Industrial Additives vs Artisan Ingredients

In mass-produced meat, you’ll often see long ingredient lists with preservatives and flavor enhancers. A classic example is sodium metabisulfite (E223), which prevents oxidation and extends storage life. You can learn more about how this additive functions on the American Institute for Cancer Research explanation of processed meat.

Traditional charcuterie doesn’t rely on additives like these. Salt, and sometimes a controlled amount of nitrate or nitrite, are the only things added to the meat. These are not meant to artificially preserve color or texture but to allow the curing process to work naturally through osmosis and moisture reduction.

To make the comparison clearer, here’s a general breakdown of what defines each approach:

| Aspect | Artisan Charcuterie | Commercial Processed Meat |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredients | Meat, salt, spices, sometimes nitrate/nitrite | Meat, water, stabilizers, binders, preservatives |

| Preservation Method | Natural drying, salt-curing, smoking | Chemical additives, heat treatment |

| Processing Time | Weeks to months | Hours to days |

| Flavor Development | Fermentation and enzymatic aging | Artificial flavoring |

| Texture | Dense, dry, layered | Soft, uniform, emulsified |

Understanding Additives and Preservatives

There’s often confusion around ingredients labeled with “E-numbers.” These codes simply represent approved food additives in Europe, ranging from harmless natural acids to synthetic stabilizers. In the world of industrial meat, they’re used to control color, texture, or bacterial growth. In artisan charcuterie, they’re rarely used, if at all.

For example, E223 (sodium metabisulfite) is a sulfur-based preservative used in some low-cost meats, whereas E251 (sodium nitrate) serves a different purpose—it helps prevent botulism in cured meats. Each has a different role and should never be treated as the same substance.

I often see confusion in how people interpret these labels. While many traditional dry-cured products do include minimal nitrates or nitrites, they’re used at safe levels that help maintain color and prevent harmful bacteria. The bigger difference lies in whether these compounds are used as part of a thoughtful curing process or as a shortcut for shelf life.

Why Charcuterie Isn’t the Same as Deli “Processed” Meat

When you compare a hand-crafted salami to a supermarket packet of “salami-style” slices, you’ll notice the difference immediately. The texture, aroma, and flavor of a true dry-cured meat develop over months of controlled fermentation and drying. Factory meats are made in days, using rapid acidification, smoke flavoring, and additives to mimic that profile.

I once examined a “salami” label from a supermarket shelf that listed meat, water, sugar, flavor enhancers, antioxidants, and stabilizers—all to achieve what simple salt and patience could have done naturally. That’s when I realized how far removed most processed meats are from the traditional roots of charcuterie.

It’s also worth remembering that these differences aren’t just culinary. They reflect how food traditions evolve under industrialization. While artisan producers lean on fermentation and natural drying, industrial processors rely on chemistry and consistency.

The result is two very different categories of food that only share a name. One has centuries of craftsmanship behind it; the other is a product of efficiency and modern manufacturing.

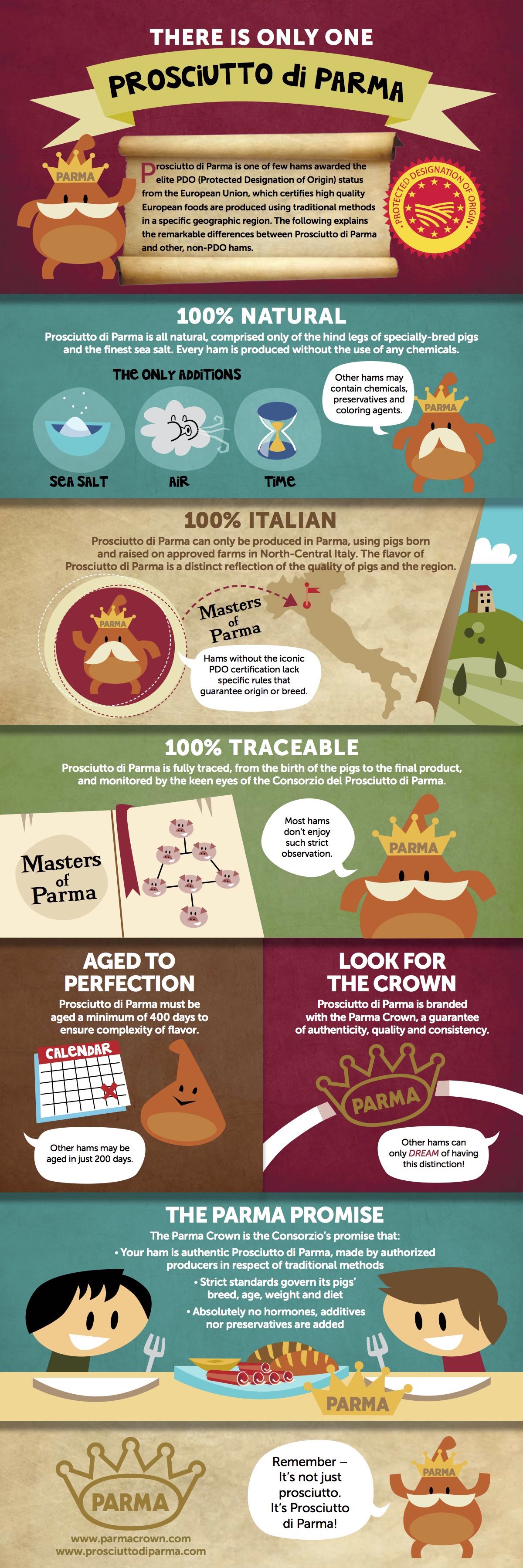

Parma Ham and the Italian Tradition

Few cured meats are as iconic as Prosciutto di Parma. When I first visited Parma, I learned that what makes it special is not complexity, but restraint. It’s made with only pork, sea salt, and time—nothing else. The skill lies in how the salt is applied and how the air is managed for the months, sometimes years, that follow.

The process starts by rubbing sea salt onto the pork leg, allowing the salt to draw out moisture and create an environment where spoilage bacteria can’t thrive. The meat is then rested and slowly dried in carefully controlled humidity. In the cool cellars of northern Italy, natural molds form on the surface, helping regulate moisture and develop aroma.

After around 12 months, the meat has lost more than a third of its weight, the texture becomes firm, and the flavor deepens into something rich and nutty. It’s sliced paper-thin, and the fat melts instantly on the tongue. This transformation is entirely natural—no additives, binders, or artificial preservatives.

That’s why I’ve never seen Parma ham as a “processed” product. It’s a preserved food, yes—but its preservation comes from time and skill, not chemicals or shortcuts. The same can be said for other dry-cured Italian meats like pancetta, coppa, and guanciale, all of which rely on salt and environment, not additives.

These principles are the foundation of dry curing, which I cover in detail in my guide on how to dry cure meat at home. Once you understand the role of salt, airflow, and temperature, you can safely replicate small-scale curing projects in your own kitchen.

Unlike modern factory meat, which may use curing accelerators or injected brines, Parma ham is a product of patience. This is why, even though both involve salt, one belongs to the world of charcuterie and the other belongs to industrial processing.

Across Italy, families still hang legs of pork in their cellars through winter, trusting the climate to do most of the work. Every region has its signature version—San Daniele, Toscano, or Speck—each slightly different in aroma and texture but bound by the same ancient logic of salt and time.

When you taste a slice of true prosciutto, it’s a window into that tradition. You’re tasting the patience of a year’s work, the clean salt from the Mediterranean, and the balance of humidity from the Italian hills. There’s no recipe that can rush that process without losing something essential.

I’ve met butchers who say they can tell if a leg will turn out perfectly just by its smell after the third month of curing. That kind of intuition comes only with years of experience and deep respect for the process. That’s not “processing”—that’s craftsmanship.

If you’d like to explore nitrate-free variations of traditional charcuterie, I’ve also written about which charcuterie meats do not have nitrates and how they compare in safety and flavor.

Whether you’re working with prosciutto, pancetta, or lonza, dry curing is always about harmony—between temperature, airflow, salt, and time. Once you understand that balance, it opens up a world of possibilities in your own curing projects.

For those wanting to start with a smaller project, curing in a kitchen fridge is a surprisingly effective approach. I’ve written a simple guide on how to cure meat in a regular fridge without modifying it, showing that even modern home setups can produce exceptional results with basic tools and patience.

All these traditional techniques share one truth: when meat is handled carefully, salt and airflow are enough. There’s no need for synthetic preservatives or additives to achieve longevity and incredible flavor.

Nitrates and Nitrites in Dry-Cured Meat

Of all the ingredients discussed in cured meats, nitrates and nitrites cause the most confusion. They’re often mentioned in the same breath as “processed” meat, but the reality is far more nuanced.

When I began studying traditional curing, I realized nitrates and nitrites weren’t invented by the food industry. They’re naturally present in vegetables, water, and soil. In fact, most of what we consume daily comes from plants, not meat.

This video gives a useful overview of how preservatives are defined and used differently across regions. It’s worth watching a few minutes to understand how labeling and perception vary between the UK and Europe.

For a deeper technical discussion, I’ve summarized key findings on my page about cured meat and nitrates. It explains where nitrates occur naturally and how traditional curing methods keep them within safe limits.

The common misconception is that nitrates and nitrites are “added chemicals.” In truth, they have been part of salt-curing for centuries, long before industrial additives existed. They stabilize color, prevent botulism, and contribute to the signature pink hue of cured pork.

What matters most is the quantity and source. Artisan producers use only trace amounts, allowing natural bacterial processes to convert nitrates slowly into nitrites over time. In commercial factories, much larger doses are added directly for speed and uniformity.

“From all the furore around processed meat, you may imagine it is the major source of nitrates in our diet. But in fact only around 5% come from this source, while more than 80% are from vegetables.”

BBC article on nitrates in food

This shows how misleading some headlines can be. The debate isn’t about whether nitrates exist—it’s about how they’re managed. In small, well-balanced quantities, they make dry curing safer without compromising flavor.

Through my experience curing hundreds of meats, I’ve found the natural equilibrium between safety and flavor is easy to maintain with precise salt ratios and the right humidity. Whether you use curing salt or only sea salt, understanding your environment matters far more than fear of chemistry.

Scientific Study of Parma Ham

One of the most interesting discoveries I came across while researching Parma ham is that science is beginning to back what artisans have known for centuries. Studies show that traditionally cured hams like Prosciutto di Parma are easier to digest and contain beneficial amino acids that develop during the long aging process.

These results make sense. Slow, natural curing gives enzymes time to break down proteins and fats gradually. This transformation not only enhances flavor but may also make the meat gentler on the digestive system compared to many modern processed foods.

You can read the official research summary in the Parma Ham Consortium’s publication, “Parma Ham: Well-being and Diet.” It explores how natural fermentation and drying create a more complex nutrient profile than heat-treated meats ever could.

In my own experience, the way these long-cured hams age mirrors what happens in cheese or wine. Every month adds depth, aroma, and subtlety. It’s the patience, not the additives, that defines the quality.

That’s also why I consider cured meats a craft worth learning hands-on. Once you understand the science of salt, air, and humidity, you realize how consistent the process can be at home. I explain every stage in my detailed guide on my online charcuterie course, which covers equipment setup, safety, and step-by-step methods.

For anyone who wants to start small, I always recommend mastering equilibrium curing first. It’s simple, safe, and helps you see how salt moves through meat over time. Once that’s clear, dry curing becomes second nature.

Over time, I’ve found that learning to cure your own meats gives you a deeper respect for food and its origins. It’s not about chasing trends or shortcuts—it’s about understanding time, fermentation, and flavor the way artisans always have.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is prosciutto considered processed meat?

Not in the industrial sense. Prosciutto is salt-cured and air-dried without synthetic preservatives. It’s preserved naturally through time, airflow, and humidity rather than chemicals or heat treatments.

Is Parma ham healthier than regular ham?

Parma ham is lower in additives and often easier to digest due to its long curing time. The natural fermentation breaks down proteins and fats, creating a complex flavor with less processing.

Does Parma ham contain nitrates?

Most traditional Parma ham uses only sea salt, but commercial versions may include trace amounts of nitrate or nitrite for consistency and safety. These levels are minimal compared to industrial processed meats.

Can I make prosciutto or cured meats at home?

Yes. With controlled humidity and temperature, it’s possible to make small-scale cured meats safely. Start with easier projects like pancetta or coppa before attempting a full prosciutto.

Have a question or want to share your own curing project? Leave a comment below — I’d love to hear how your charcuterie journey is going.

Tom Mueller

For decades, immersed in studying, working, learning, and teaching the craft of meat curing, sharing the passion and showcasing the world of charcuterie and smoked meat. Read More