Nitrites are often described as a preservation tool, but in practice their role in meat curing is far more specific. In my own curing projects, nitrites are primarily about colour development and colour stability, not whether meat can be cured successfully.

The confusion usually starts when nitrites are treated as “the cure,” rather than as an optional curing agent used in certain styles of curing.

The confusion comes from treating nitrates and nitrites as the curing process itself, rather than as curing agents used within certain processes.

Salt, time, and moisture loss are what actually cure meat, whether it is dry cured or wet cured.

Nitrates and nitrites do not replace those fundamentals; they are added for specific functional reasons such as colour stability in cooked products, speeding up curing reactions, or improving consistency in long brined meats.

This distinction matters because, in my experience, meat curing works perfectly well without nitrites and always has.

Salt, time, meat quality, patience, observation, accurate process control rather than guesswork, and good hygiene are the real foundations of curing.

Why Nitrites Are Used in Cured Meats

Nitrites become relevant when appearance, uniform colour, or cooked outcomes are part of the goal. This is where their functional role starts to matter.

Colour Development and Stability in Cured Meats

One of the most visible effects of nitrites is colour. When nitrites are used, cured pork retains a stable pink hue instead of turning grey or brown during cooking.

This is one of the main reasons nitrites are used so widely in commercial products.

Pink ham or bacon is simply easier to sell than a grey version, even when both are cured correctly.

This colour change is often mistaken for preservation or safety, but visually it is simply a reaction between nitrites and the meat’s myoglobin.

I’ve also come across plain sea salts that naturally contain trace nitrates, as well as traditional additives like potassium nitrate, commonly known as saltpetre.

In small amounts, these can act as curing agents and influence meat colour, even when no modern curing salt is intentionally added.

This helps explain why colour changes can still occur in curing projects that appear nitrate-free on the surface.

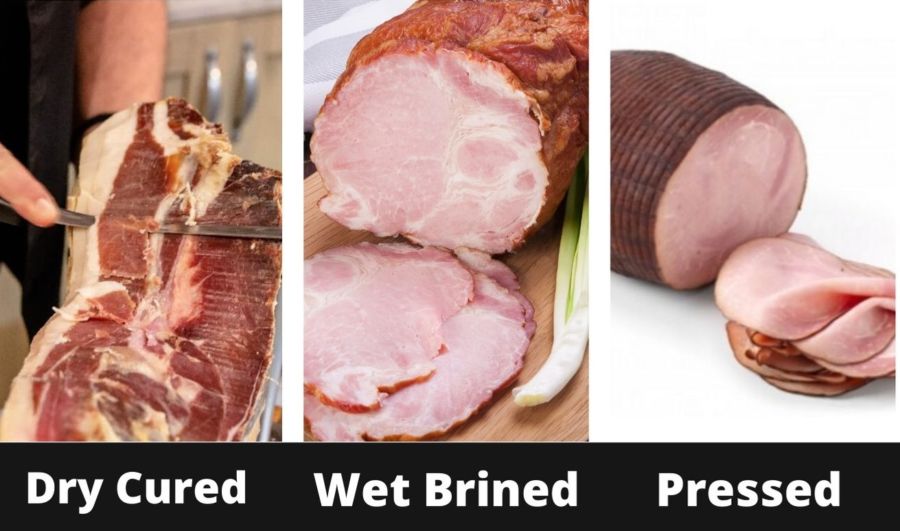

In dry-cured meats such as prosciutto, lonza, or bresaola, colour stability is not required.

These products are not cooked, and their natural colour evolution is part of the tradition.

Dry curing often produces darker red or deep crimson tones, particularly in pork.

Why Nitrites Are Used for Cooked and Hot-Smoked Hams

Nitrites become functionally useful when meat is cured and then cooked, particularly in hot-smoked or fully cooked hams.

These products are often brined for long periods and then taken through cooking or smoking steps that would otherwise cause the meat to turn grey.

In this context, nitrites help maintain the familiar pink colour people associate with ham.

Without them, a cooked ham or bacon can look visually unappealing, even when the curing process itself has been carried out correctly.

This is a functional and aesthetic decision rather than a requirement for curing itself.

Dry Curing Without Nitrites as a Traditional Process

Long before modern curing salts were commercially available, dry curing relied entirely on salt, airflow, temperature, and time.

The preserving effect came from salt dispersing evenly through the meat, followed by controlled drying.

In some cases, cold smoking was also used, which can introduce mild natural fermentation during or shortly after the salting stage.

Whole-muscle dry curing developed in regions without refrigeration, and nitrites were not intentionally added.

The success of these traditional methods came from controlling moisture loss and allowing salt to penetrate the meat slowly and evenly.

This is still how dry curing works today, whether nitrites are used or not.

When I dry cure prosciutto, bresaola, pancetta, or dry-cured salami without nitrites, nothing fundamental changes in the process.

The same attention to humidity, airflow, and patience is required.

As a simple visual example, dry-cured whole muscle colour can look very different to wet-brined, cooked, nitrite-cured ham.

What Changes When Nitrites Are Not Used

The most noticeable difference when nitrites are left out is visual rather than structural.

In wet cures or long brines, curing time can increase slightly because nitrites help speed up certain curing reactions.

This is one reason they are common in commercial ham production.

In dry curing, time is already a core part of the process, so this difference is rarely meaningful.

Flavour development is driven far more by drying, enzymatic breakdown, and aging than by the presence or absence of nitrites.

I’ve seen claims online of a “porkier” flavour from nitrites, but I have not found clearly defined research supporting this.

What Does Not Change in Dry Curing

One of the biggest misconceptions about curing without nitrites is that the process itself changes.

In reality, the fundamentals of dry curing remain the same.

Salt still diffuses into the meat and binds at the cellular level.

Moisture still moves out over time.

Nitrites may influence colour and certain reactions, but they do not replace salt diffusion, drying, or environmental control.

Moisture Loss and Water Activity

Meat curing succeeds or fails based on the intended outcome.

For dry curing or preservation, salt penetrates the meat and moisture is slowly removed, limiting the conditions that allow spoilage.

For cooked or hot-smoked products, brining helps retain moisture closer to the surface during cooking.

Salt concentration determines whether moisture continues to move out of the meat or is held closer to the surface.

Nitrites do not change these physical processes.

This is why equilibrium curing works reliably with or without curing salts.

Salt Penetration and Flavour Development

Salt penetration is controlled by thickness, temperature, and time, not by the presence of nitrites.

Flavour development during dry curing comes from enzymatic breakdown and aging rather than curing salts.

This is why many traditional dry-cured meats develop depth and complexity without relying on nitrites at all.

Why Traditional Dry Curing Never Needed Nitrites

Traditional dry curing evolved around environmental control rather than chemical intervention.

Regions known for dry-cured meats relied on seasonal temperatures, steady airflow, and salt availability, with documented practices dating back well before the Common Era.

Whole-muscle cuts were chosen because they dried predictably and resisted spoilage when handled correctly.

These methods depend on understanding how meat behaves over time.

They do not depend on nitrites in order to function.

Where People Get Tripped Up Going Nitrite-Free

Most problems people experience when curing without nitrites are not caused by their absence.

Colour variation, darker tones, and uneven shading are normal outcomes of traditional dry curing.

Applying wet-brining or cooked-meat expectations to dry curing is where confusion usually starts.

Why the Botulism Conversation Derails Online

Nitrites are often discussed in relation to botulism, and that association can make people treat nitrites as if they are the “definition” of safe curing.

In my experience, this is where nuance gets lost, because people mix together very different products, processes, temperatures, and storage conditions under one label.

If you are unsure about any curing method, follow established guidance for your region and keep your process tightly controlled.

How I Decide Whether Nitrites Belong in a Project

I don’t start with trends or ideology.

I begin with the outcome I want.

This dictates the process and the craft.

Dry-cured meats and cooked or hot-smoked hams are fundamentally different outcomes, even though both use salt.

Based on my own experience and further research, I tend to use nitrites for dry-cured salami and for brined, hot-smoked projects where fat behaviour, colour, and consistency matter.

Dry-Cured, Uncooked Meats

For whole-muscle dry curing where the meat is never cooked, nitrites are not something I automatically reach for.

These projects rely on gradual moisture loss, controlled airflow, and time.

The colour, texture, and flavour evolve naturally as the meat dries.

Cooked and Hot-Smoked Hams

When a project involves long brining followed by cooking or hot smoking, nitrites become a practical tool.

They help deliver the familiar pink colour and consistent results people expect from cooked ham.

Tradition, Appearance, and Personal Preference

Choosing whether to use nitrites often comes down to tradition and preference rather than necessity.

Some curing styles prioritise visual consistency.

Others embrace natural variation as part of the craft.

Neither approach is inherently better.

Keeping dry-curing and cooked-ham projects clearly separated makes decisions around curing salts much simpler.

Alternatives to Nitrites in Dry Curing

Ingredients such as celery powder or beetroot are sometimes used as “natural” alternatives, but at a molecular level, they still introduce nitrates or nitrites.

In practice, this distinction is often more about marketing than process.

Are nitrites required for dry curing meat?

Nitrites are not required for traditional dry curing of whole-muscle meats. Products such as Prosciutto di Parma are made using only pork and salt, relying on moisture loss, airflow, skill, and time rather than curing salts.

Why do some cured meats turn grey when cooked?

When cured meat is cooked without nitrites, the natural pigments in the meat change colour, often resulting in a grey or brown appearance. This is a visual change rather than a failure of the curing process.

Do nitrites speed up dry curing?

Nitrites can shorten curing time in brined or wet-cured products. In traditional dry curing, time is already a core part of the process.

Why are nitrites commonly used in cooked or hot-smoked hams?

Nitrites are used in cooked or hot-smoked hams to maintain a stable pink colour and consistent results after long brining and cooking. Their role is largely functional and aesthetic.

If you’ve experimented with curing meat with or without nitrites, or noticed differences in colour or drying outcomes, leave a comment below and share what you’ve observed.

Tom Mueller

For decades, immersed in studying, working, learning, and teaching the craft of meat curing, sharing the passion and showcasing the world of charcuterie and smoked meat. Read More