Having made and experienced every style of ham, I wanted to clarify some aspects that are often confused.

“Cured” ham refers to a process where salt is used to transform the meat.

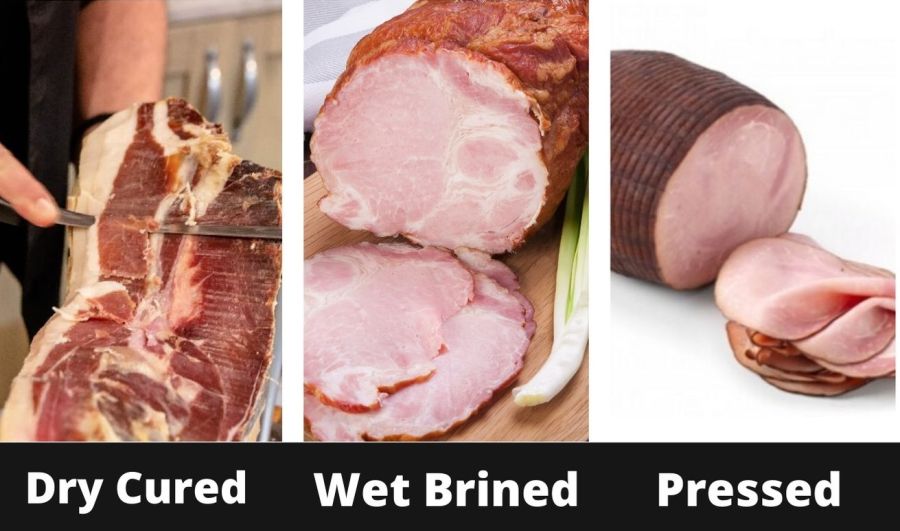

From there, methods branch: slow dry-curing and aging, quicker brine-&-cook styles, smoke as a layer, or pressed/formed deli styles. This table gives you the lay of the land before we dive into specifics.

| Ham Category | How It’s Made (short) | Salt Method | Smoking | Cooked? | Typical Time | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salt Dry Cured Whole Muscle | Salted, equalized, air-dried/aged | dry | Sometimes | No | 12–60+ months | Prosciutto di Parma, Jamón Ibérico, Jambon de Bayonne, Westphalian, Dalmatinski pršut |

| City / whole cured (brined then cooked) | Immersion brine or injection; often tumbled; then hot-smoked or cooked to serving temp | Wet | Wet Brine/injection | Yes | Days to weeks | Holiday ham, Smoked Berkshire-style ham |

| Country ham (US dry-cured) | Dry salt cure, rest/age, often smoke; usually cooked before serving unless sliced very thin | Dry | Cold smoke | After aging | 2–6+ months | Virginia/Kentucky country ham, Smithfield style |

| Pressed / formed deli ham | Chopped, extraction, tumbling, molded | Wet | Cooked / Hot smoked | Yes | 1–3 days | Deli ham, luncheon ham, ham steak |

I’ve made and tasted my way through many of these styles. The most significant differences you’ll notice at the table—beyond flavor—are texture and moisture. Dry-cured hams slice paper-thin and melt; city hams are juicier and ready right after cooking; pressed hams are uniform and slice neatly for sandwiches.

What follows in this guide: first the long, traditional dry-cured path (salt application, equalization, aging, and optional smoke), then the brined-and-cooked styles, and finally the pressed/formed category so you can read labels and choose quality with confidence.

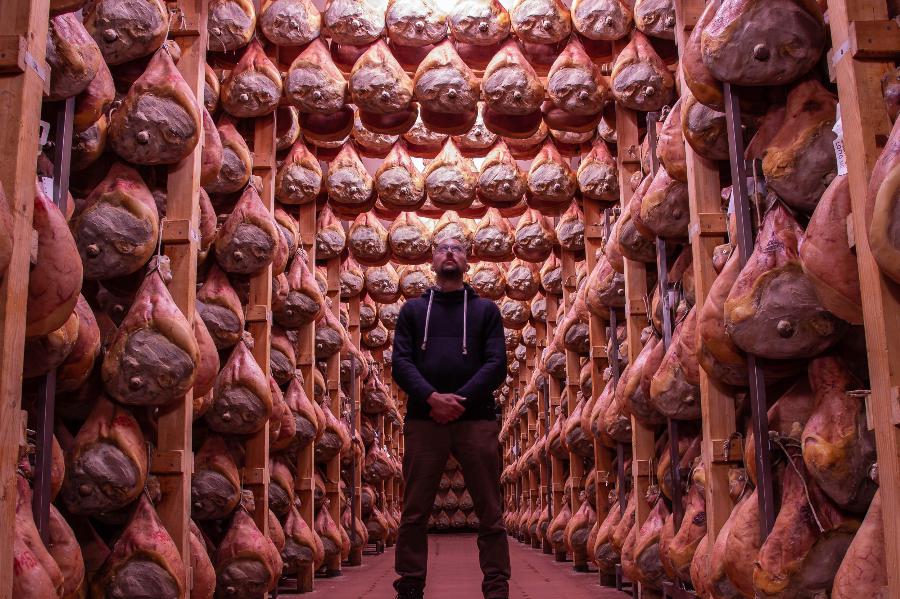

Dry-Cured Hams: The Long, Traditional Path

Dry-cured ham is the patient route: salt first, then time, airflow, and gentle conditions. No cooking; the transformation comes from salt and controlled drying. Think prosciutto, jamón, Bayonne—paper-thin slices, deep aroma, clean finish.

Salt Application: Saturation vs Equilibrium

Every dry-cured ham starts with salt. You’ve got two practical ways to get it into the meat: the old-school saturation (excess-salt “saltbox”) approach, and the more measured equilibrium method (salt as a % of meat weight). If you want a primer on what “dry-cured” actually means across bacon, ham, and sausage, I break that down here: What is Dry Cured Meat?

Equilibrium curing hits a predictable salt level for balanced flavor and consistent results—my go-to when I want control on smaller projects and trial batches. Full walkthrough, percentages, and workflow: Complete guide to equilibrium curing.

Saturation (saltbox) curing surrounds the ham with excess salt. It’s robust, traditional, and common for large whole legs. Expect a saltier profile unless carefully managed; it’s the historical backbone of many regional hams. Method details here: Traditional saltbox dry-curing.

Equalization: Letting Salt Distribute

After salting, the meat rests to allow salt to migrate evenly. This equalization step prevents a salty exterior with a bland center. On large legs, the rest can be substantial; on smaller muscles, it’s shorter. Either way, patience here pays off in uniform flavor and a cleaner, more even dry.

Drying & Aging: Temperature, Humidity, Airflow

Once salt is in balance, the ham moves into steady conditions. I aim for a cool environment and moderate humidity so moisture leaves slowly and evenly. Too dry and you risk a hard shell; too wet and surfaces can struggle. I’ve laid out practical targets and dialing strategies here: Temperature & humidity for a meat-curing chamber.

You don’t need a full chamber for every project. For small, lean cuts, a carefully managed home fridge can work surprisingly well if you control surface moisture and airflow. My no-mod method is here: How to cure meat in a regular fridge.

Time does the rest. Proteins tighten, flavors concentrate, and aroma develops. This is where dry-cured hams earn their reputation: the slow shift from “pork” to “prosciutto/jamón”—a different food entirely.

Optional Cold Smoking (Regional Styles)

Some traditions add a phase of cool, gentle smoke (below 30 °C / 86 °F) after salting and resting. The goal isn’t cooking—just subtle phenolics, surface drying, and a regional signature (think Westphalian or lightly smoked coastal styles). Fruitwoods and beech are common; airflow and clean, smoldering smoke matter more than heavy intensity.

Examples You’ll Recognize

Prosciutto di Parma — salt, time, and air, with strict rules and long aging. The official consortium explains the process clearly: Prosciutto di Parma (Consortium overview).

Jamón Ibérico — long aging and acorn-fed pork in its top expressions; deep color and aroma.

Bayonne / Westphalian / Dalmatinski pršut — regional salts, breezes, and sometimes a gentle smoke give each its accent—different routes; same craft.

That’s the dry-cured family: salt first, then months to years of careful drying. Next we’ll look at the brined-then-cooked path (often hot-smoked): faster timelines, juicier slices, and a very different texture in the mouth.

City/Whole Cured Hams (Brined, Then Cooked or Hot-Smoked)

This family is the “holiday ham” most people know. The cure is applied with water (a seasoned brine), and then the ham is cooked—often while being hot-smoked. It’s faster than dry-curing, juicier by design, and very label-driven: how the brine gets in, how much, and what happens after all change the texture and flavor.

Immersion Brine vs Injection

Immersion brine is the slow lane. The leg sits in a salty, seasoned solution and diffusion does the work. It’s gentle and even, but time-hungry on a whole leg.

Injection uses multi-needle pumps to push brine into the muscle. It’s fast and consistent for large pieces, but can tip toward watery, one-note flavor if overused. Many commercial hams combine injection with a short soak so the brine equalizes inside the meat before cooking.

Either route relies on good formulation: salt level for flavor and preservation, a touch of sugar for balance, spices for character, and (in many products) curing salts and phosphates for color, safety margin, and moisture retention.

Tumbling & Protein Extraction

After brining, producers often tumble the meat in a rotating drum. The mechanical action extracts myosin (a “sticky” muscle protein) that helps bind pieces, improve sliceability, and retain moisture during cooking. It’s a valuable tool; when pushed too far, it’s how you end up with a bouncy, uniform texture that tastes more of brine than pork.

It’s also used to speed up salt /dry wet curing for dry-cured bacon, for instance.

Cooking & Hot Smoking: What Changes in the Meat

Hot smoking cooks and flavors at the same time. You’ll see honey-glazed, maple, or hickory-leaning finishes—these ride on top of the brine profile. A roasted city ham skips smoke and goes straight to gentle cookery. Either way, the result is ready-to-eat, sliceable, and best served slightly warm or at room temperature for full aroma.

Compared to dry-cured ham, the texture stays juicier, and the grain of the meat is more apparent. Good examples feel plush and carve cleanly; poor examples weep water and shred.

Warm Smoking vs Hot Smoking

Producers sometimes use a lower chamber temperature (warm smoking) early, then finish hotter to set the protein. This staggers smoke uptake and avoids a tough exterior. Full hot smoking throughout is faster and common for mass production. Both approaches are valid; what matters is even doneness and clean, thin smoke—never acrid or heavy.

Pressed / Formed Deli Hams (How They’re Made)

Pressed hams don’t mimic a single muscle. Trims or chunked pieces are brined/injected, then tumbled to extract enough myosin for binding. The mixture is stuffed into a mold, net, or casing, set with heat, and cooled. It slices neatly for sandwiches and can be excellent when the inputs are honest and the brine is restrained.

When cost-cutting dominates, you’ll taste it: rubbery chew, briney aftertaste, and “water rings” on the slicer. Those aren’t flaws of the category; they’re production choices.

What the Label Quietly Tells You

City and pressed hams of mass production are sometimes. A few phrases decode quality fast:

- “Added water” / “water product” — expect higher juiciness but lighter flavor; often lower price point.

- “With natural juices” — typically less added water; better odds of clean texture.

- “Chunked and formed” / “restructured” — pressed ham; look for tidy slices without excessive purge.

- Ingredient list length — shorter usually tastes more like pork; long lists flag heavy functional additives.

For the eater, the test is simple: does it slice clean, hold its shape, and taste of seasoned pork rather than brine? If yes, you’ve got a good city ham. If not, you’re paying for water and process.

Serving Notes from the Bench

I let cooked hams lose their chill before carving—aroma and texture bloom as the surface warms. Glazes are optional; if you use one, keep it thin so you don’t lacquer over the ham’s natural character. Leftovers? Dice into beans or lentils; the brined, smoky notes are built for them.

Next up: a quick guide to ingredients & label clues across every ham style—and a few regional examples so you can spot honest craft on the shelf.

Ingredients, Additives & Label Clues

Across every style, salt leads. From there, what producers add (or don’t add) explains why one ham tastes like concentrated pork and another like brine. Here’s how to read what you’re buying.

Salt, Sugar & Spices

Salt drives curing, flavor, and moisture change. A little sugar rounds edges (not to make it “sweet” so much as to balance salt). Spices (pepper, bay, juniper, garlic) create regional accents without hiding the pork.

Nitrite/Nitrate (Why Ham is Pink)

Many cured hams include curing salts (nitrite/nitrate). Besides an added safety margin in specific styles, they fix the familiar rosy color and a characteristic cured aroma. Long-aged, traditional hams may rely on salt and time alone; cooked/brined products commonly use curing salts for stability and color consistency.

Some sea salt has a degree of natural nitrite and the pinkness does come through.

Phosphates & Added Water (City/Pressed Hams)

Phosphates help retain moisture by improving water binding. They’re common in brined and pressed hams. More added water usually means juicier texture but lighter flavor; it also inflates weight. The label tells you which way the product leans.

- “Added water/water product” — higher moisture, softer bite; often lower price.

- “With natural juices” — typically less added water; cleaner texture.

- “Chunked & formed/restructured” — pressed ham; look for neat slices without excessive purge.

- Short ingredient list — more pork-forward; long lists flag heavy functionality.

FAQ

Is all ham cured?

No. In the U.S., a fresh, uncured pork leg can be labeled “fresh ham.” Most products called ham are cured (dry or brined), but labeling matters.

Is ham always smoked?

No. Many iconic hams (Parma, Serrano, Bayonne) are not smoked. City hams are often hot-smoked; some dry-cured regional styles use a light cold smoke.

Why is ham pink?

Curing salts (nitrite/nitrate) commonly used in many hams fix a rosy color and cured aroma. Long-aged salt-only hams can be red to ruby without added curing salts due to slow drying and pigment changes.

How long does a dry-cured ham take?

From about 12 months for classic prosciutto styles to 24–60+ months for certain jamón grades. City/pressed hams are measured in days or weeks, not years.

Questions or experiences with a regional ham style? Drop them in the comments—I read every one.

Tom Mueller

For decades, immersed in studying, working, learning, and teaching the craft of meat curing, sharing the passion and showcasing the world of charcuterie and smoked meat. Read More