Charcuterie encompasses a vast array of preserved meats, and most of them can be traced back to the pig. Across Europe, pork has long been the foundation of cured meat making—whether sliced paper thin like prosciutto or packed into a rustic salami. Over the years I’ve worked with all kinds of meats, but pork still stands out for how forgiving and flavorful it is when cured properly.

People often think of charcuterie as a single category of food, yet it’s more a craft built around fat, salt, and time. Pork fits perfectly into that equation.

It has the right balance of lean and fat, the right texture, and the right neutral flavor that allows subtle seasoning or smoke to shine through. That’s why even modern interpretations of charcuterie still lean heavily on pork, while beef, duck, or venison appear as interesting exceptions rather than the rule.

Why Pork Became the Foundation of Charcuterie

When I first began dry-curing meats, I noticed that pork behaved differently from everything else. The fat didn’t oxidize or turn overly strong in flavor during the long drying phase. In fact, after months of curing, the flavor stayed rich and balanced rather than gamey or sour. That’s the main reason traditional charcuterie across Europe relies so much on pork—it simply cures better.

Historically, the pig offered more than just meat. Its fat, organs, and skin were all preserved in some form. Farmers could transform an entire animal into sausages, hams, terrines, and rillettes that lasted through winter.

Unlike cattle or game, pigs were easily raised in small villages and could be processed without the need for large smokehouses or refrigeration. That practicality became the base of what we now call classic European charcuterie.

Fat Quality and Flavor

Pork fat has a neutral, clean flavor with a relatively high melting point. When cured, it becomes silky rather than greasy, coating the palate with richness instead of heaviness.

In dry-cured salami, I always aim for about 25 percent firm back fat; it keeps the texture tender once moisture is lost. Other animal fats can go rancid more quickly or add an unwanted aftertaste, but pork fat ages gracefully. That single property shapes the mouthfeel of almost every traditional cured meat.

Preservation and Texture Benefits

Beyond flavor, pork muscle structure is ideal for equilibrium curing. The balance of water and protein allows salt to penetrate evenly, minimizing spoilage and creating a consistent texture.

Whether I’m hanging a whole hind leg for prosciutto or curing a smaller coppa cut, the results are predictable. The even grain and firm connective tissue help each piece lose moisture at a steady rate, something that’s much harder to achieve with leaner meats like venison or beef.

That even drying makes it possible to slice pork charcuterie paper-thin without it crumbling. It’s the reason deli counters everywhere can shave prosciutto into translucent ribbons that practically melt on the tongue. Few other meats deliver that combination of stability, beauty, and flavor once cured.

From Farm Tradition to Modern Boards

The evolution from farm preservation to the modern charcuterie board happened naturally. What once kept families fed through winter now appears in restaurants and homes as a celebration of craftsmanship. Every prosciutto, pancetta, or coppa still carries the same balance of salt, time, and pork fat that rural butchers perfected centuries ago. When I visit small European towns, I still see hams hanging in cellars and pancetta tied with twine—proof that these methods endure because they work.

In today’s kitchens, pork charcuterie bridges the gap between tradition and convenience. Even supermarket versions echo old techniques, though often accelerated. True cured pork, however, rewards patience: months of slow transformation that turn a fresh leg or belly into something complex, sliceable, and shelf-stable without any modern additives.

Classic Pork Charcuterie Meats and Cuts

After years of experimenting with different animals, I’ve learned that pork offers the widest range of possibilities for curing. Each muscle reacts differently to salt, time, and airflow, producing distinct flavors and textures. The Italians call this full collection of cured pork salumi. From the jowl to the hind leg, almost every part of the pig can be transformed into something delicious and long-lasting.

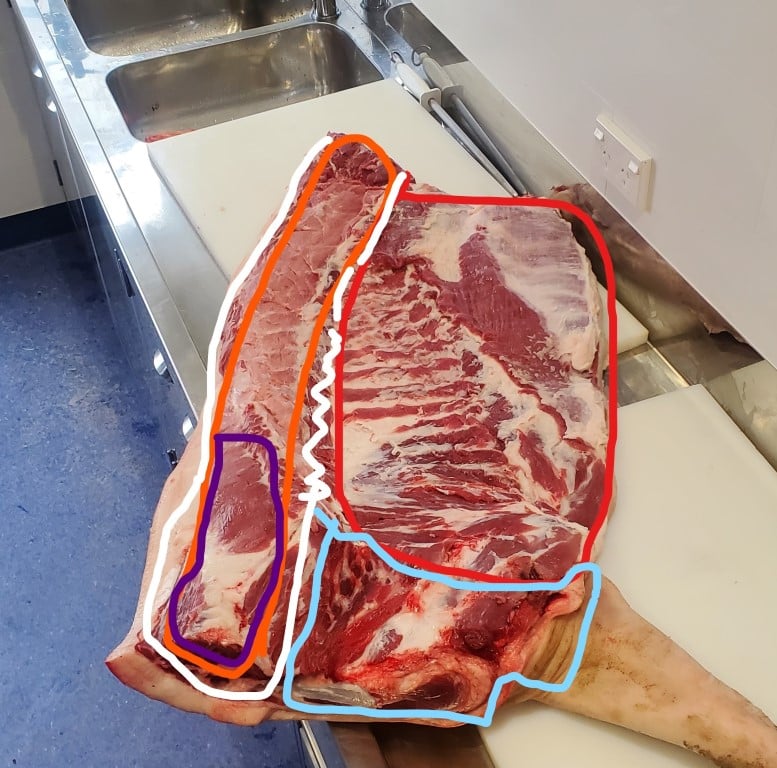

To make it easier to visualize where these cuts come from, here’s a simple overview of the classic Italian whole-muscle charcuterie meats and the area of the pig they come from. These are the same cuts I use when planning my own dry-curing projects.

| Charcuterie Cut | Part of Pig |

|---|---|

| Guanciale | Jowl or Cheek |

| Coppa / Capocollo | Upper Loin to Shoulder |

| Lonza / Lonzino | Loin |

| Spalla | Front Leg / Shoulder |

| Pancetta | Belly |

| Culatello | Boned Hind Leg |

| Prosciutto | Hind Leg (Bone-In) |

Each region of Italy has its own interpretation of these same cuts. The technique might shift slightly—spices, smoking, or casing style—but the foundation remains salt and time. In the north, curing is often slower and drier; in the south, warmer climates shorten drying and add chili or fennel for extra flavor. I’ve always appreciated how predictable pork muscle is when hanging in the curing chamber—it loses moisture steadily without collapsing or cracking.

Whole-Muscle Pork Charcuterie

Whole-muscle cures showcase the natural grain of the meat. Cuts like coppa and lonza develop marbling that looks almost like wood grain once sliced thin. I normally cure them for 30 to 60 days depending on size and humidity. The aroma that comes out of the chamber toward the end has that nutty, slightly sweet scent that only pork fat can create. Prosciutto or culatello, of course, are far longer projects—anywhere from 12 to 24 months depending on weight and bone structure.

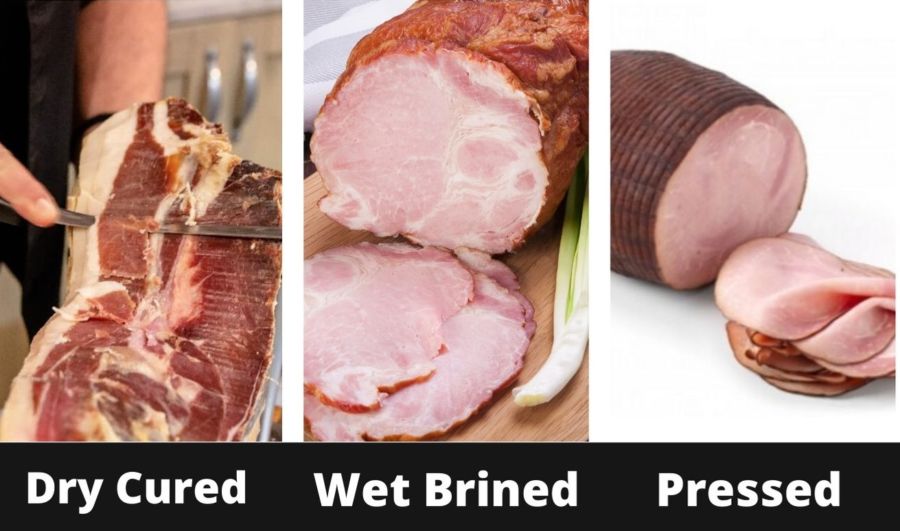

Prosciutto is probably the best-known example. When I toured producers in Parma, the entire process felt almost ceremonial: salting, resting, washing, and hanging in airy rooms for up to two years. Every step depends on controlling temperature and humidity rather than rushing with heat or additives. That approach is what defines real charcuterie versus quick-processed ham.

Salami and Emulsified Sausage Styles

Once the trimmings and lean pieces are ground and mixed with salt and spices, they become the foundation for salami. A proper dry-cured salami relies on around one-quarter pork fat to maintain moisture and texture. I’ve found back fat cubes of 8–10 mm give the best definition after drying—small enough to slice easily but large enough to keep their integrity. Without that fat, salami becomes dry and crumbly instead of smooth and balanced.

Traditional Italian salami such as soppressata, Felino, or Picante are aged for months, not weeks. Each region adds its own twist—some include red wine, others garlic or

French and Central & Eastern European Pork Charcuterie

Traditional Italian salami such as Soppressata, Felino, or Picante are aged for months, not weeks. Each region adds its own twist—some with red wine, others with garlic or fennel. When dried slowly, the pork fat stays defined and creamy instead of turning oily.

Across France, the word charcuterie takes on a broader meaning. It covers everything from sliced ham to pâtés and terrines. Most of them are still built around pork.

French Pork Classics

French producers rely on salt, spice, and gentle heat instead of pure air-drying. You’ll find jambon sec (dry-cured ham), rillettes preserved in fat, and coarse country terrines. Each one uses the pig from nose to tail.

Rillettes are slow-cooked shreds of pork shoulder packed under a thin layer of fat. Terrines combine minced meat and liver set with gelatin. Both are sliced cold and spread onto bread—rich, savory, and unmistakably pork.

Jambon de Bayonne represents France’s answer to prosciutto. Salted, rested, and dried for nearly a year, it has a gentle sweetness that balances the salt. Paris ham, by contrast, is wet-cured and cooked, served as soft slices rather than air-dried pieces.

Central & Eastern European Pork Traditions

Move east from France and Italy, and the curing style changes completely. Cold smoke becomes the main preservative. Garlic and paprika replace pepper and wine.

In Poland, boczek—smoked pork belly—is rubbed with salt and marjoram before hanging over beechwood smoke. It’s rich and slightly chewy, perfect for slicing thin over rye bread.

Hungary’s kolbász blends pork, paprika, and garlic, then dries slowly until firm. The smoke adds color as well as protection. Czech and Slovak kitchens cure and smoke šunka or údené mäso, keeping them for months through winter.

I’ve seen small smokehouses in mountain villages where pork shoulders and hams hang for weeks. Temperatures hover around 20 °C, letting the smoke layer slowly rather than cook the meat. The result is dense, dark, and deeply aromatic.

These traditions favor robustness over delicacy. Fat is celebrated, not trimmed. Cracklings become škvarky; rendered fat turns into spreads similar to French rillettes. Every part of the pig serves a purpose.

Texture and Flavor Differences

Western European pork charcuterie aims for subtle sweetness and silky texture. Central and Eastern versions chase smoke, garlic, and spice. One melts on the tongue; the other fills the room with its aroma.

Both styles rely on the same principle—use the whole pig, cure with care, and respect the time it takes. Pork remains at the heart of every method, linking farm traditions from France to Slovakia under one shared craft.

Non-Pork Charcuterie and Using Pork Fat for Balance

While pork dominates traditional charcuterie, many other meats cure beautifully when handled with the same respect for salt, air, and time.

Over the years, I’ve cured venison, beef, duck, and even lamb. Each behaves differently in the chamber, and each benefits in some way from a little help from pork fat.

Beef and Venison Charcuterie

Lean red meats like beef and venison dry fast. They lack the intramuscular fat that keeps pork supple, so the texture can tighten quickly if humidity drops too low.

I’ve had good results with whole-muscle cuts such as eye of round for bresaola-style cures or wild venison hind leg trimmed carefully. The flavor is deeper and slightly metallic compared with pork, but a small coating of fat helps keep the surface from drying too hard.

Duck, Lamb, and Goat

Duck breast cures quickly and needs only light drying. Its fat behaves differently—it melts at a lower temperature—so shorter drying times prevent rancidity.

Lamb and goat have stronger aromas that develop rapidly under salt. A short equilibrium cure followed by gentle cold smoking can mellow the flavor while still preserving the meat.

Why I Still Use Pork Fat

Even when I work with other meats, I often blend in pork back fat. It brings moisture retention, structure, and that signature smooth mouthfeel missing from leaner animals.

In dry-cured sausages, 20 to 30 percent pork fat is enough to bind the mix and prevent case hardening. Without it, the result can taste dry or chalky.

When making venison or beef salami, I keep the pork fat chilled to avoid smearing. Once ground and mixed, it becomes visible white flecks that hold their shape through the entire drying process.

Balancing Flavor and Tradition

Non-pork charcuterie opens new flavor paths—gamey, smoky, earthy—but pork still acts as the foundation that ties them together. A touch of its fat rounds off sharp edges and brings familiarity to something new.

Whether I’m hanging wild venison in a home curing fridge or slicing thin duck prosciutto, the same principle applies: respect the meat, manage humidity, and let time do the work. Pork may not be the only choice, but it remains the standard by which all cured meats are measured.

Expert Tip

When curing lean or wild meats, always keep the fat component cold before grinding or mixing. Firm pork back fat cuts cleanly and prevents smearing, giving you those distinct white specks once dried. If the fat warms up, it blends into the meat and ruins both flavor and texture.

For equilibrium cures, weigh everything carefully—salt, sugar, and curing time depend on exact ratios. Precision is the difference between consistent, professional results and unpredictable outcomes.

Alternatives

If pork is off the table, consider combining lean game meats with a small portion of duck fat or beef tallow. Both give body and slow moisture loss, though neither matches the stability of pork fat during long drying cycles.

Short-term projects like duck breast prosciutto or spiced beef bresaola deliver deep flavor in a few weeks rather than months. They’re excellent introductions to non-pork charcuterie while you refine your setup and technique.

What meats can replace pork in charcuterie?

Beef, venison, duck, and lamb can all be cured successfully. Each requires adjusted drying time and salt level to avoid toughness. Fat from duck or beef can help replace pork fat, but expect stronger flavors and faster drying.

Why is pork fat still used in most recipes?

Pork back fat stays stable during long cures, resists rancidity, and provides smooth mouthfeel. Even small amounts blended into lean meats improve texture and flavor balance.

What is an easy non-pork meat to start curing?

Dried beef, bresaola, or duck breast prosciutto are ideal. They cure quickly, need minimal equipment, and help you understand humidity control before tackling longer projects.

Have any questions about curing non-pork meats or balancing fat ratios? Drop a comment below — I’d love to hear what projects you’re working on.

Tom Mueller

For decades, immersed in studying, working, learning, and teaching the craft of meat curing, sharing the passion and showcasing the world of charcuterie and smoked meat. Read More

Nice article. Thanks. Love the passion of this craft, in SA we starved of availability of equipment. And we starve ourselves of the flavours and go to the graves with uneducated taste sensors.

Ostrich! I have heard of many SAers is the best Biltong! We keep it pretty simple around here in New Zealand. Check out this post about converting a fridge – https://eatcuredmeat.com/how-to-build-a-curing-chamber-for-dry-cured-meat/

Cheers Tom