What goes into curing meat? Whether you’re making prosciutto, jerky, bacon, or bresaola — it all comes down to a few essential ingredients.

After decades of experimenting with cold smoking, dry curing, and fermented salami, I’ve learned how these ingredients work together to preserve meat, bring out incredible flavor, and have different outcomes.

This article breaks down the main ingredients used across different curing methods and explains how each one functions. From salt and sugar to curing salts and acids — if it’s in the cure, it’s here.

Main Ingredients for Curing Meat

1. Sea Salt – The Base of All Cures

It’s the oldest and most essential component — used in everything from prosciutto to pastrami to salmon gravlax.

Sea salt serves multiple purposes.

It pulls moisture out of the meat through diffusion, creating an environment less hospitable to bacterial growth through binding. In equilibrium curing, the salt also stabilizes moisture levels, allowing the meat to cure more evenly over time.

It also contributes to forming the pellicle — a tacky surface protein layer that’s essential for proper smoke adhesion in both cold and hot smoking. Without salt, the meat won’t preserve or take on that deep, smoky flavor many of us love.

Not all salts are ideal, though. I stick with unrefined sea salt or kosher salt, which are free from additives. Table salt can contain anti-caking agents or iodine, which can interfere with curing or leave off-flavors.

I wrote this article on salt for meat curing here.

2. Curing Salt – When and Why It’s Used

Known by many names – Pink Curing Salt, Prague Powder, Instacure, Instamix and more.

These all contain a precise percentage of sodium nitrite or nitrate — depending on the type — mixed with regular salt (which makes up 90% of the curing salt.

All of these have a No. 1 version that is used for short-term cures under 30 days, especially when the meat will be cooked afterward. Also, a No. 2 version for long-term dry curing, like prosciutto or fermented salami, where nitrate breaks down into nitrite over time.

These curing agents help prevent the growth of bacteria like Clostridium botulinum, speed up the curing process, and contribute to the iconic pink color of many cured pork products.

Because the amounts needed are very small — often just a few grams per kilogram of meat — I always use a precision digital scale down to 0.01g.

It’s also essential to store the curing agent salt clearly labeled and far away from everyday cooking salt to avoid confusion. It’s bright pink, often, so make sure it’s not confused with regular salt.

Some producers avoid using curing salts altogether, opting for traditional methods with only sea salt in certain countries. That’s totally fine for specific styles, as long as the risk factors are understood and properly managed.

Some confusing packaging legislation was passed, uncured meats for commercial sale in America use natural forms of nitrates/nitrites. They have the same effects as synthetically created.

I believe it’s a personal choice for the home curer.

3. Sugar – For Balance, Color, and Fermentation

Sugar isn’t always included, but it plays an important supporting role in many cures. It helps balance out the saltiness, assists with browning during cooking (like in bacon), and even helps feed lactic acid bacteria in fermented salami.

Depending on the style and regional tradition, you’ll see sugar in the form of white sugar, brown sugar, maple syrup, honey, or even molasses. It’s especially common in wet brines for hams and poultry, or in American-style bacon cures.

When using equilibrium curing, I typically calculate sugar as a small percentage of the total meat weight — usually somewhere between 0.5% and 2%, depending on how sweet or balanced I want the end result.

Sweeteners also pair well with pork and can enhance the aroma and complexity of the finished product when smoking or aging.

4. Acidity – Vinegar, Wine, and Citrus in Meat Curing

Acidic ingredients like vinegar, wine, and citrus are used in several curing styles to inhibit bacteria and add distinct flavor. While not as universally used as salt or sugar, acidity plays an important role in jerky, biltong, and fermented salami.

In biltong, for example, malt vinegar is used to denature the surface proteins of the meat and lower the pH. This not only preserves but also gives that signature tangy flavor. Jerky recipes sometimes include soy sauce, Worcestershire, or citrus juice for similar effects — adding acidity and helping with shelf life when cooking isn’t enough.

Wine is another acidic ingredient, traditionally used in Italian-style salami making. It provides mild fermentation support and flavor complexity, especially when combined with garlic and pepper.

The acidity can help balance sweetness and saltiness, while also acting as a natural preservative — especially important in air-dried meat curing where moisture and temperature must be carefully controlled.

Starter Cultures & Mold – Advanced Fermentation Tools

For dry-cured salami and more advanced air-dried projects, I often use starter cultures like Bactoferm. These contain beneficial bacteria that drop the pH quickly during fermentation, making the meat safer to dry and less prone to spoilage.

Some cultures also enhance flavor or speed up drying. The type of bacteria you use (such as pediococcus or lactobacillus) affects the tang, dryness, and aroma of the salami or cured sausage.

I also use mold cultures like Penicillium nalgiovense sprayed on the outside of salami. This white mold helps control moisture loss, prevents unwanted mold growth, and gives that beautiful white bloom you see on artisanal cured meats.

To learn more about how these techniques work together, here’s my guide to dry curing meat that explains the full process.

5. Spices & Herbs – Flavor and Function

Once you’ve nailed salt and safety, spices and herbs are where you can really get creative. Whether you’re making classic pancetta, smoky jerky, or a fusion-style dry-cured ham, these ingredients define the final aroma and taste.

But spices do more than flavor. Many have antimicrobial properties that contribute to preservation. Garlic, black pepper, paprika, chili, coriander, juniper, bay leaf, and rosemary are all common for a reason — they each offer functional and aromatic value.

For example, garlic has long been associated with reducing bacterial growth. Chili can help dry out the surface. Black pepper adds subtle heat while helping form a protective outer layer when aging whole muscles like bresaola or lonza.

I’ve put together a detailed herb and spice pairing guide as part of my meat curing course, and I’ll be including a downloadable version in this article soon to help with your own creations.

If you’re curious about the differences between curing styles and how ingredients vary, check out this article on types of meat curing.

5. Smoke – Hot and Cold Smoking

It’s odd to list this as an ingredient, but it is. Smoking wood for cold or hot smoking has different effects.

For Hot Smoking, it’s about cooking and flavoring at the same time. This is always done at lower cooking temperatures, in traditional Eastern European culture – there is also warm smoking meats which occur between hot and cold smoking temperatures.

Cold Smoking is about the smoke flavor – but traditionally it was the antimicrobial benefits that helped protect and preserve the meat as well.

For more on cold smoking, I’ve written many articles – here is a link to the category to browse.

The beginners’s guide page with articles linked for cold smoking is here.

How Ingredient Use Changes by Curing Method

Now that we’ve looked at the core ingredients, it’s helpful to understand how they’re used differently across the main styles of meat curing. Some methods require only salt, while others rely heavily on nitrites, acidity, or added cultures.

This is where technique meets ingredient choice — and knowing what works best in each style helps avoid mistakes, waste, and safety risks.

Dry Cured Whole Muscle

This style includes meats like pancetta, bresaola, coppa, and lonza. The process is simple in concept — apply a salt-based cure, optionally add sugar or spices, and hang the meat to dry slowly over several weeks or months.

In most cases, I use just sea salt and spices. Pink curing salt is optional here, depending on your risk tolerance and climate. I’ve had great success with and without it, but I always focus on humidity control and proper airflow to keep the meat safe.

Common spice blends for whole muscle cuts (pork/beef) include black pepper, juniper berries, garlic powder, and bay leaves. They don’t just smell good — they also discourage surface mold and create flavor depth during aging.

For anyone curious about the entire process from trimming to drying, I’ve broken it down fully in this guide to dry curing meat.

Dry Cured Salami

Salami is one of the most ingredient-dependent and technically sensitive curing methods. You’ll need finely ground meat and fat, mixed with salt, pink curing salt No. 2, sugar, spices, and a fermentation culture to safely drop the pH before drying.

Pink curing salt No. 2 is essential here because the drying process exceeds 30 days. It prevents the growth of dangerous bacteria like botulism and gives the salami its reddish interior.

Starter cultures are also non-negotiable. I use Bactoferm T-SPX or similar strains to ferment the meat and drop the pH quickly after stuffing — usually within 24 to 72 hours. This step makes the meat shelf-stable and safe to air-dry over the following weeks.

Spices in salami vary wildly by tradition — fennel, garlic, chili flakes, black pepper, white wine, and even nutmeg depending on the regional recipe. Many of them are functional as well as flavorful.

If you’re curious about the nitrate/nitrite science behind salami safety, check out this post on understanding nitrates in cured meats.

Cold Smoked Meats

Cold smoking adds smoke flavor over time without cooking the meat, which means proper curing and drying must come first. For food safety, I always dry cure the meat with either just salt or a mix that includes pink curing salt No. 1 — especially when smoking pork.

Salt creates the pellicle needed for smoke to adhere properly. Sugar helps with color and balances the sharpness of the smoke. If you’re curing belly or loin for bacon, pepper, paprika, or bay leaf are all common additions before it hits the smokehouse.

Unlike hot smoking, cold smoking is a preservation technique — not just flavor. That’s why I always cold smoke over multiple sessions (sometimes 12–48 hours total) after curing and drying.

Want to learn more about how I cold smoke safely? Here’s my full guide to cold smoking meat.

Jerky & Biltong

Jerky and biltong are unique because they often combine curing with light cooking or air drying — and rely on acidity more than nitrates. In most cases, pink curing salt is not used, though some commercial recipes may include it.

For jerky, I usually use a marinade with salt, soy sauce, garlic, smoked paprika, and something acidic like Worcestershire or citrus. It’s then dried at a low temperature in a dehydrator or oven — more of a cooking step than traditional curing.

With biltong, I cure the meat first using sea salt and malt vinegar, then hang to air-dry over several days. Coriander seed, black pepper, and a little sugar are classic flavor additions. The acidity from vinegar is key to both flavor and safe drying.

If you want to try either style, here’s a simple walkthrough I put together for making jerky and biltong at home.

Each method has its own ingredient needs, and when you understand how they work, you can confidently cure and flavor meat to your style without compromising safety or taste.

More Flavor Combinations

Once you’ve mastered the fundamentals of curing ingredients, the fun part begins — customizing flavors to suit your taste, your region, or your favorite traditions. Whether it’s fennel seed in Italian salami, smoked paprika in bacon, or malt vinegar in biltong, the possibilities are endless.

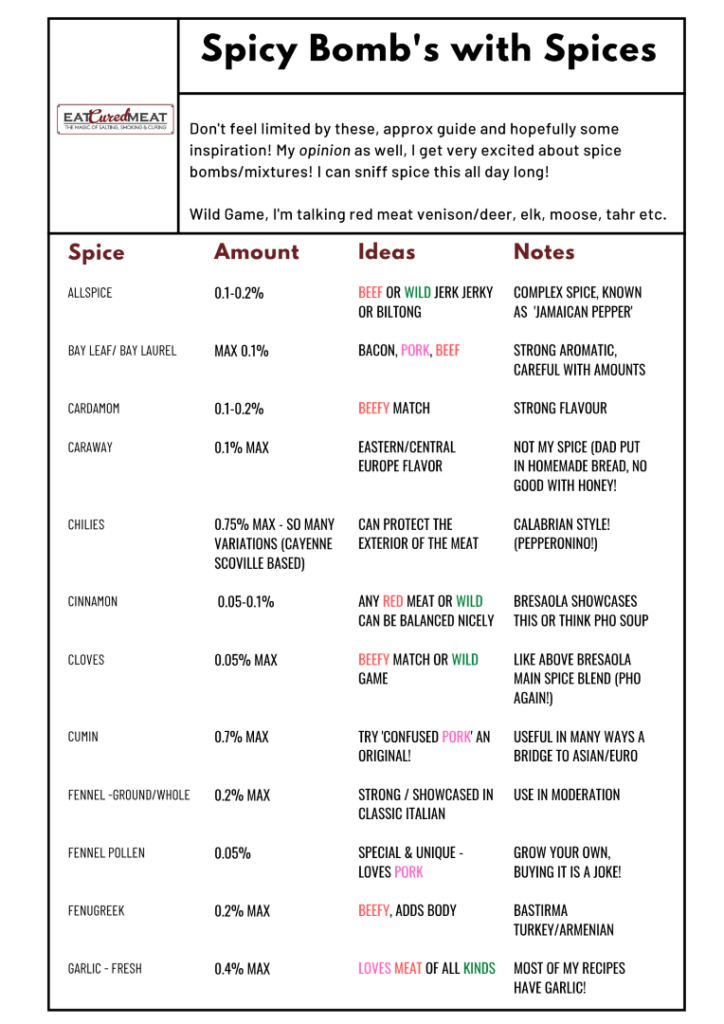

In one of my online courses, I put together a detailed spice and herb pairing sheet that covers spice amount recommendations based on meat type:

Tip: Use Precision for Safety and Consistency

When using pink curing salt, accuracy matters. Since you often measure in small fractions of a gram, I always use a digital scale with 0.01g precision. This helps you avoid over- or under-curing and ensures you stay within safe nitrate/nitrite limits for both short- and long-term cures.

Can You Cure Without Pink Salt?

Absolutely — many traditional methods use only sea salt and careful drying. I’ve dry-cured plenty of pancetta and coppa using just salt and spices. However, risk tolerance and conditions are important.

What is a Meat Cure Made Of?

Meat curing can mean several things. Salt is always included, since it has the primary effect, depending on the technique, of trying to preserve or hold moisture during the cooking/hot smoking process.

What is the most essential ingredient for curing meat?

Salt, specifically sea salt or kosher salt without additives or anti-caking agents, is the primary ingredient for curing meat. Depending on the curing method, it plays a critical role in preservation by inhibiting harmful bacteria, retaining moisture, or aiding in drying the meat.

What are the differences between Pink Curing Salt No. 1 and No. 2?

Pink Curing Salt No. 1 contains sodium nitrite and is used for curing projects under 30 days, such as bacon or corned beef. Pink Curing Salt No. 2 includes sodium nitrate, which gradually converts to sodium nitrite over time, making it ideal for long-term curing projects like prosciutto or salami.

Can curing meat be done without nitrates or nitrites?

Yes, curing meat without nitrates or nitrites. It’s done personally and commercially across the world. Care is needed all aspects is necessary, especially the quality and handling of the meat.

Do you have a question about an ingredient? Drop a comment below.

Tom Mueller

For decades, immersed in studying, working, learning, and teaching the craft of meat curing, sharing the passion and showcasing the world of charcuterie and smoked meat. Read More