Cured meats often get lumped in with “processed meats,” and that’s where a lot of confusion starts. I’ve been curing and tasting these products for decades, and I’ve learned that words matter. Precise definitions help people appreciate the craft, the ingredients, and the time that go into traditional cured meats.

This article clearly breaks down the terms. First, I define what cured meat is. Then, I explain what processed meat means in a broader sense. From there, it becomes much easier to see why some cured meats are craft-focused while others are designed for speed and uniformity.

What is Cured Meat?

Cured meat is meat preserved with salt. That’s the foundation. Everything else—spices, airflow, temperature, and time—sits on top of that foundation to produce flavor, texture, and aroma.

There are two big families: whole-muscle cures and comminuted cures. Whole-muscle cures are cuts like pork leg for prosciutto or beef eye of round for bresaola. Comminuted cures involve ground or chopped meat, such as salami and other fermented styles. Both can be traditional and artisanal, but the handling and goals differ.

Definition & Techniques

At its core, curing is about salt drawing out moisture and creating an environment that is inhospitable to spoilage. In traditional practice, I weigh the meat, calculate the salt, and let time do its work under controlled conditions. Temperature is kept calm and steady. Humidity is managed to prevent the outside from drying too quickly. Airflow is gentle and consistent rather than gusty or stagnant.

Some projects are simple salt-and-meat; others fold in spices to build a regional or house style. Peppercorns, garlic, chili, and herbs aren’t there just for perfume. They can contribute subtle functional benefits while defining the final character of the meat.

Traditional Examples

Prosciutto, culatello, coppa, pancetta, bresaola, and many regional salumi represent classic whole-muscle and fermented traditions. They are often minimalist by design. The focus is on the animal, the cut, the salt, and the slow transformation that happens with patience and good conditions.

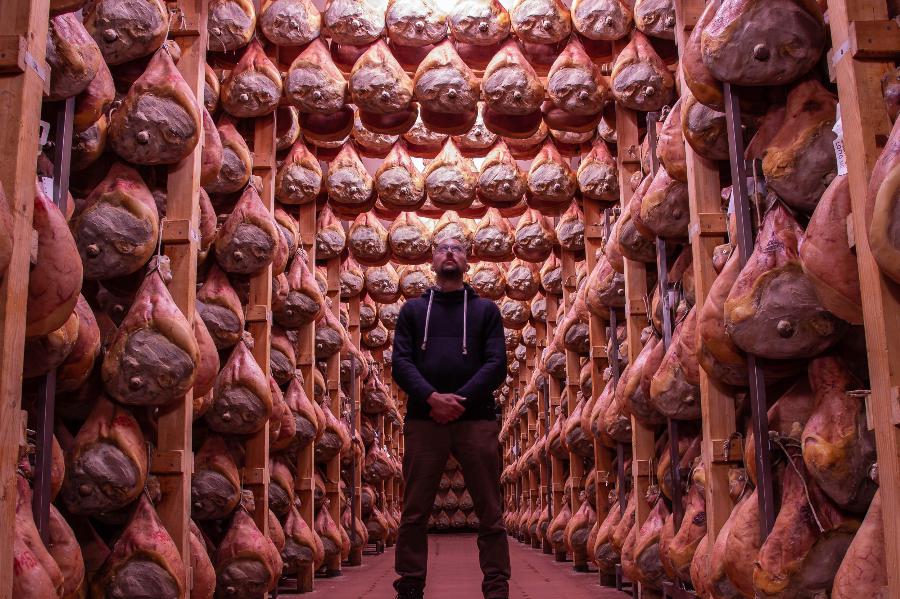

When I visit traditional producers or hang my own projects, the aim isn’t to make every slice identical. It’s to arrive at balance—savory depth, gentle sweetness, clean fat, and a texture that slices beautifully. That balance takes months, not days.

Role of Salt, Airflow, and Time

Salt is the non-negotiable. It sets the stage for preservation and flavor development. Airflow keeps the surface in the proper condition; too much and the outside crusts, too little and you risk sluggish drying. Time is the quiet partner that integrates everything. Rushing the process usually shows up on the plate—uneven texture, flat flavor, or a harsh, salty edge.

When all three work in concert, you get balance and nuance. That’s the difference between “meat that’s been salted” and cured meat with real character.

What is Processed Meat?

Processed meat is a broader umbrella. It generally covers meat that has been transformed beyond its fresh state through techniques such as curing, smoking, cooking, fermenting, or adding other ingredients. By that broad definition, many cured meats fall within the “processed” category—alongside products that differ significantly in purpose and formulation.

This is where confusion starts. People hear “processed” and picture hot dogs or bologna. But the term also encompasses traditional cured specialties. The outcomes can share a category name while being worlds apart in craft, ingredient lists, and timeframes.

Regulatory Definitions

Food agencies use practical, catch-all definitions to classify the various ways meat is altered from its fresh state. These definitions are applicable for labeling and oversight, but they don’t always reflect the nuance between a month-long ham and a fast, additive-heavy lunch meat. That nuance is what I focus on throughout this piece.

Examples

Under this broad umbrella, you’ll find bacon, deli cuts, cooked sausages, hot dogs, canned meats, and many convenience products. Some are simple; many are formulated for speed, shelf stability, or absolute consistency. That’s not automatically “bad,” but it does shift priorities away from the long, slow development I value in traditional curing.

Why “Processed” is a Broad Category

“Processed” groups together very different products because it describes what has been done to the meat, not the intention behind it. A whole muscle that’s salted and air-dried for many months and a fast-tracked, additive-rich product can both meet the definition. From a cook’s perspective, they are nothing alike. From a regulatory perspective, they sit under the same roof.

Understanding that distinction helps you read labels with more confidence and appreciate why some cured meats taste so layered and distinct.

The Key Differences: Curing vs Processing

Now that the terms are defined, it becomes clearer how curing and processing diverge. Curing is a craft-driven method that relies on time, salt, and patience. Processing, in its broader commercial sense, often prioritizes speed, efficiency, and uniform results. Both approaches preserve meat, but the paths and outcomes are very different.

Ingredients Used

Minimal salt and spices

Traditional curing often uses just pork and salt, sometimes with a few spices or herbs. I’ve worked with black peppercorns, garlic, chili, and rosemary to create different styles, but these additions are minimal. The salt does the preservation work, and the other ingredients contribute flavor and regional character. This is why two prosciuttos from different valleys in Italy can taste distinct despite sharing the same fundamentals.

Additive-rich commercial recipes

Commercially processed meats often include long ingredient lists: phosphates for moisture retention, nitrites for speed and color, sugars, flavor enhancers, and stabilizers. These are designed to make the product consistent and fast to produce. For instance, commercial vs artisan salami ingredients highlight just how different the recipes can be when speed and efficiency are the goals.

Methods and Timeframes

Slow traditional curing

Artisanal projects can take months or even years. Prosciutto di Parma, for example, isn’t rushed; it develops flavor slowly while drying and maturing in carefully managed conditions. The long process is what gives depth, complexity, and that distinctive clean finish. I’ve always found that time is the most important ingredient in this style of curing.

Accelerated industrial processing

Commercial methods use shortcuts. Acidifiers lower pH quickly, additives hold water, and mechanical processes push the meat through production lines in days or weeks rather than months. The result is predictable flavor and texture, but much less variety or individuality compared to traditional cured meats.

Flavor and Variation vs Consistency

With traditional curing, no two batches are identical. Climate, airflow, breed, and artisan handling all leave a mark. That variety is often the joy of tasting cured meats—layers of character that reflect the place and the process.

Commercial processing flips the goal. Every package of hot dogs or deli ham is expected to taste the same, whether you buy it in New York or New Zealand. Uniformity becomes the measure of success, not distinctiveness. That’s a valuable trait for mass retail but far from the craft-driven charm of traditional curing.

Common Misconceptions Busted

“All cured meat is processed”

This statement is both accurate and misleading. Technically, curing is a form of processing. But when people use “processed,” they often mean factory-made, additive-heavy products. That’s where the confusion lies. Articles like what cured meat actually means help clear up the definition gap.

“Uncured” label means additive-free

Products labeled “uncured” often use celery powder or other natural nitrate sources instead of synthetic nitrites. Legally, they can call it “uncured,” but chemically, it’s performing the same role. It’s a labeling loophole more than a fundamental difference.

“Processed equals low quality”

Not all processed meat is low quality. Traditional cured meats technically fall into the processed category, but they’re often produced with care, select cuts, and minimal ingredients. On the other hand, many industrial products are driven by efficiency and profit. The key is knowing how to distinguish between them when reading labels or tasting.

Cured Meat in Context: Taste, Craft, and Perception

Why artisanal cured meats are valued

When you eat a slice of prosciutto, culatello, or bresaola that’s been hanging for months, you’re tasting tradition and patience. These products cost more due to the time, skill, and quality of the meat involved. They’re valued for character, not uniformity.

Nitrates and nitrites in perspective

Nitrates and nitrites often cause concern, but context matters. Leafy vegetables naturally contain many times more nitrates than cured meats. The body also produces nitrates on its own. Research like this EFSA overview on nitrates and nitrites helps put their role in perspective.

Some charcuterie traditions avoid added nitrates altogether. If you’re curious, see this breakdown of charcuterie meats made without added nitrates for examples of how different producers approach the craft.

Enjoyment, tradition, and moderation

From my perspective, the best way to frame cured meats is through enjoyment and tradition. They are foods with deep cultural roots and incredible flavor when made with care. Moderation and appreciation are more useful lenses than labeling them “healthy” or “unhealthy.”

Traditional vs Commercial Curing

Time and Method

Traditional curing is measured in months or even years. Cuts are salted, rested, and then exposed to carefully managed air and humidity. The idea is to let natural enzymes and microbes slowly shape the texture and flavor. I’ve seen prosciutto houses check each ham monthly to ensure even drying, a rhythm that respects the pace of the meat itself.

Commercial curing flips the priority. Preservatives and acidifiers push the process into days or weeks. Meats might be mechanically injected or tumbled to speed up absorption. The outcome is quick turnaround and consistent appearance, but without the layered depth that slow maturation creates.

Ingredients in Depth

Salt is the anchor of traditional curing. Additions like peppercorns, garlic, fennel, or chili are chosen for flavor, not for processing convenience. These seasonings tie the product to a region or artisan’s style.

Commercial recipes rely heavily on additives. Alongside salt, you’ll often see phosphates added to retain water, dextrose or corn syrup used for balance, and stabilizers to maintain texture. Flavor enhancers keep every bite uniform. I covered this contrast in detail in my piece on commercial vs artisan salami ingredients.

Quality of Meat and Sourcing

In traditional curing, quality is non-negotiable. Parma Ham is a good example: only pigs from certain regions with specific feed are permitted, and only sea salt is used. This level of control ensures flavor and reputation.

Commercial production usually takes a broader approach. Cuts are selected for availability and efficiency rather than strict breed or feed rules. The focus is on yield and supply chain rather than regional identity. That doesn’t always mean poor quality, but it means different priorities drive the decisions.

Regional Influences

Traditional curing is inseparable from the place. Climate, air, and local customs all shape the outcome. Northern Italian prosciutto, Spanish jamón, and Central European speck are as much cultural artifacts as food. Each reflects centuries of adaptation to local environments.

Commercial products tend to erase these distinctions. Whether in North America, Europe, or elsewhere, a package of sliced ham from a supermarket aims to taste and look the same everywhere. That global consistency is a strength for distribution but a loss in cultural character.

Examples That Make It Obvious

Hot Dogs (commercially processed)

Hot dogs highlight how additives dominate commercial formulations. According to the National Hot Dog & Sausage Council, common ingredients include sodium nitrite, phosphates, corn syrup, soy protein, maltodextrin, and artificial flavorings. These keep the texture uniform and shelf life predictable. They are the definition of processed meat designed for mass markets.

Prosciutto di Parma (traditional cured)

By contrast, Prosciutto di Parma carries the Protected Designation of Origin (DOP) seal. The ingredient list is short: pork and salt. The process is long, involving salting, resting, drying, and maturing for at least 12 months. The Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma oversees these standards to maintain authenticity. What you taste is clean, savory, and deeply tied to place and tradition.

Setting these two examples side by side makes the difference obvious. One is built around efficiency and uniformity, while the other is built around heritage and patience. Both are technically processed, but only one reflects centuries of craft.

Expert Tips from My Experience

Over the years I’ve found that learning to read labels is the fastest way to spot the difference between traditional cured meats and commercial processed ones. If the ingredient list has more than a handful of items, especially with chemical names, you’re looking at a processed product designed for efficiency. If it lists only meat, salt, and maybe a spice, you’re likely holding something closer to the artisanal tradition.

Another tip is to pay attention to texture. Traditional cured meats often slice more delicately and may have variation in color or marbling. Commercial products usually look identical slice to slice. That uniformity can be convenient, but it comes at the expense of natural variety.

Alternatives Worth Exploring

If you enjoy cured meats but want to branch out, there are plenty of regional varieties to try. Spanish jamón, Italian speck, French saucisson, and Central European hams all show how different cultures adapt the same basic method. Each region has its own salt levels, spice blends, and drying traditions. Exploring these is one of the best ways to appreciate the depth of this craft.

Are all cured meats considered processed?

Yes, technically, cured meats are classified as processed because they are altered from their fresh state. However, the key difference lies in how they are made: traditional curing relies on time and salt, whereas commercial processing often adds numerous artificial ingredients.

What is the main difference between artisanal cured meat and factory-processed meat?

Artisanal dry-cured meats use minimal ingredients and long maturation times to develop flavor naturally. Factory-processed meats prioritize speed and uniformity, using additives to ensure consistent taste and texture.

Does ‘uncured’ on a label mean no nitrates or nitrites?

Not exactly. ‘Uncured’ products often use natural nitrate sources like celery powder instead of synthetic nitrites. They still perform the same role in preservation, but the label can give a misleading impression.

Why are traditional cured meats often more expensive?

They take months to produce, require careful handling, and often use higher-quality animals and cuts. That time and care adds cost, but it also creates deeper flavor and cultural value.

I’d love to hear your thoughts—do you prefer the heritage of slow-cured meats or the convenience of modern processed products? Drop a comment below and join the discussion.

Tom Mueller

For decades, immersed in studying, working, learning, and teaching the craft of meat curing, sharing the passion and showcasing the world of charcuterie and smoked meat. Read More